Friday, July 15, 2011

History of Muslim Philosophy

The interest of Western scholars in the development of Islamic philosophical thought has been comparatively small. There appear to be two reasons for this neglect: the nature of the subject matter and the character of Western scholarship itself. The main body of Islamic thought, in so far as it has any relevance outside the scope of Islam, belongs to a remote past. In fact, as this book will show, Islamic philosophy is and continues to be, even in the twentieth century, fundamentally medieval in spirit and outlook. Consequently, from the time of Thomas Aquinas and Roger Bacon until now, interest in this thought has been cultivated in the West only in so far as it could be shown to have a direct or indirect bearing on the development of European philosophy or Christian theology. More recently, attempts have been made by Western scholars to break away from this pattern and to approach Islamic philosophy as an intellectual concern in its own right, but the fruits of these efforts remain meager compared to the work of scholars in such cognate fields as the political, economic, and social development of the Muslim peoples.

Second, we note the radically modern direction that philosophy has taken in the West, from the seventeenth century on. Fresh attempts are continually being made to formulate a coherent world view for modern man, in which the role of ancient (Greek) and medieval (both Arabic and Latin) thought is progressively ignored or minimized. In this way Islamic philosophy suffers the same fate as European medieval philosophy. Furthermore, the role that Arabic philosophy played in preserving and transmitting Greek thought between A.D. 800 and 1200 has become much less significant for Western scholarship since the recovery of the original Greek texts.

It can hardly be denied that the system of ideas by which the Muslim peoples have interpreted and continue to interpret the world is relevant to the student of culture. Nor is the more abstract, formulation of this system, in theology or metaphysics, devoid of, intrinsic value. For it should be recalled that Greek philosophy, in which modern Western thought has its origins, has played a crucial role in the formulation of Islamic philosophy, whereas it has made almost no impact on other cultures, such as the Indian or Chinese. This consideration alone should be sufficient to reveal the close affinities between Islamic and Western thought.

The first important modern study in the general field of Arabic philosophy is Amable Jourdain’s Recherches critiques sur l’âge et l’origine des traductions d’Aristote et sur Ies documents grecs ou arabes employés par Ies docteurs scholastiques, which appeared in 1819. This book helped to underscore the influence of Arabic philosophy on Western, particularly Latin, scholastic thought. It was followed in 1852 by Ernest Rénan’s classic study, Averroês et I’averroïsme, which has since been reprinted several times. In 1859 appeared Solomon Munk’s Mélanges de philosophie juive et arabe, a general survey of Jewish-Arabic philosophy which is still of definite value. Early in the twentieth century appeared T. J. de Boer’s Geschichte der Philosophie in Islam (1901), which was translated into English in 1903 and continues to be the best comprehensive account of Islamic philosophy in German and English. A more popular but still useful survey, Arabic Thought and Its Place in History by de Lacy O’Leary, appeared in 1922. The many surveys by Carra de Vaux, G. Quadri, and L. Gauthier are listed in the Bibliography.

We must mention, however, three historical narratives which appeared in very recent years. M. Cruz Hernandez, Filosofia hispano-musulmana (1957), though primarily concerned with Spanish-Muslim philosophy, contains extensive and valuable accounts of the major “Eastern” philosophers and schools. W. Montgomery Watt’s Islamic Philosophy and Theology (1962), which is part of a series entitled “Islamic Surveys,” is weighted in favor of theology and therefore does not add much to our knowledge of Islamic philosophy. Henry Corbin’s Histoire de la philosophie islamique (1964), though very valuable, does not recognize the organic character of Islamic thought and tends to overemphasize the Shi’ite and particularly Isma’ili element in the history of this thought. M. M. Sharif’s History of Muslim Philosophy is a symposium by a score of writers and lacks for this reason the unity of conception and plan that should characterize a genuine historical survey.

In the field of Greco-Arab scholarship, Islamic philosophy owes much to the studies of Richard Walzer, now available in the one-volume Greek into Arabic (1962), and to the critical editions of texts prepared by M. Bouyges, S.J. (d. 1951) and ‘Abdu’l-Rahman Badawi. Bouyges made available to scholars, in the Bibliotheca Arabica Scholasticorum, a series of fundamental works in unsurpassed critical editions. A. R. Badawi has edited, over a period of two decades, a vast amount of philosophical texts which have considerably widened the scope of Arabic philosophical studies. As for the Ishraqi tradition, Henry Corbin is a pioneer whose studies will probably acquire greater signif1cance as the post-Averroist and Shi‘ite element in Muslim philosophy is more fully appreciated. Finally, the studies of L. Gardet, Mlle. A. M. Goichon, L. Gauthier, I. Madkour, S. van den Bergh, G. C. Anawati, S. Pines, M. Alonso. and L. Massignon are among the most important contemporary contributions to the study of Muslim thought; these books are listed in the Bibliography.

An argument against the attempt to write a general history of Islamic philosophy might be based on the fact that a great deal of the material involved must await critical editions and analysis before an attempt can be made to assess it. I believe that this objection is valid in principle. However, a fair amount of material is now available, either in good editions or manuscripts, and the collation of the two should make interpretation relatively accurate. More over, the writing of a general history that would give scholars a comprehensive view of the whole field is a prerequisite of progress in that field, since it is not possible otherwise to determine the areas in which further research must be pursued or the gaps which must be filled.

We might finally note that the writing of a history of philosophy, as distinct from a philosophical chronicle, must involve a considerable element of interpretation and evaluation, in addition to the bare narrative of events, the listing of authors, or the exposition of concepts; without such interpretation the dynamic movement of the mind, in its endeavor to comprehend the world in a coherent manner, can scarcely be understood. In taking this approach a writer might find it valuable to reexamine areas which others have studied before him. In this hazardous undertaking I have naturally tried to learn as much as possible from other scholars. However, in the exposition of philosophical concepts or problems I have relied primarily on the writings of the philosophers themselves. Sometimes the interpretation of philosophical or theological doctrines has compelled me to turn to the studies of contemporary authorities. I did not feel, however, once those doctrines had been sufficiently clarified, that it was necessary to multiply these authorities endlessly. The purpose of the Bibliography at the end of the book is to acquaint the interested reader with the work of other scholars in the field and to indicate the extent of the material used in the writing of this book.

I wish to acknowledge my debt to the many persons and institutions that have made the publication of this work possible. In particular, I thank the librarians at Istanbul, Oxford, the Escorial, Paris, London, the Vatican, and the Library of Congress who have generously given their assistance. To the Research Committee and the Arabic Studies Program of the American University of Beirut I am particularly indebted for financing the research and travel that I did in connection with writing large parts of this book. To the Publications Committee of this University I am indebted for a generous subsidy to meet the editorial costs of preparing the manuscript for press. I also wish to thank the former Dean of the School Arts and Sciences of the American University of Beirut, Professor Farid S. Hanania, for his encouragement in the early stages of writing the book, and Professors Arthur Sewell and David Curnow for their help in editing the manuscript, at least up to Chapter Seven. And to the many unnamed scholars and colleagues, from whose advice and criticism I have profited more than I can say, I extend a warm expression of thanks. Finally to Georgetown University I am grateful for assistance in the final preparation of the manuscript and the opportunity, while engaged in teaching, to complete the last chapters of this book, and to the staff of Columbia University Press for their courtesy and efficiency in producing this volume.

Tuesday, July 12, 2011

History of Egypt

The Nile has been the lifeline for Egyptian culture since nomadic hunter-gatherers began living along the Nile during the Pleistocene. Traces of these early people appear in the form of artifacts and rock carvings along the terraces of the Nile and in the oases.

Along the Nile, in the 12th millennium BC, a grain-grinding culture using the earliest type of sickle blades had been replaced by another culture of hunters, fishers, and gathering people using stone tools. Evidence also indicates human habitation and cattle herding in the southwestern corner of Egypt, near the Sudan border, before 8000 BC. Geological evidence and computer climate modeling studies suggest that natural climate changes around 8000 BC began to desiccate the extensive pastoral lands of northern Africa, eventually forming the Sahara (c.2500 BC). Early tribes in the region naturally tended to aggregate close to the Nile River where they developed a settled agricultural economy and more centralized society. There is evidence of pastoralism and cultivation of cereals in the East Sahara in the 7th millennium BC.

Continued desiccation forced the early ancestors of the Egyptians to settle around the Nile more permanently and forced them to adopt a more sedentary lifestyle. However, the period from 9000 to 6000 BC has left very little in the way of archaeological evidence.

Predynastic period

Main article: Predynastic Egypt

Further information: Naqada

A Naqada II vase decorated with gazelles, on display at the Louvre.

By about 6000 BC, organized agriculture and large building construction had appeared in the Nile Valley.[1] At this time, Egyptians in the southwestern corner of Egypt were herding cattle and also constructing large buildings. Mortar was in use by 4000 BC. The Predynastic Period continues through this time, variously held to begin with the Naqada culture.

Between 5500 and 3100 BC, during Egypt's Predynastic Period, small settlements flourished along the Nile, whose delta empties into the Mediterranean Sea. By 3300 BC, just before the first Egyptian dynasty, Egypt was divided into two kingdoms, known as Upper Egypt, Ta Shemau, to the south, and Lower Egypt, Ta Mehu, to the north.[2] The dividing line was drawn roughly in the area of modern Cairo.

The Tasian culture was the next to appear in Upper Egypt. This group is named for the burials found at Der Tasa, a site on the east bank of the Nile between Asyut and Akhmim. The Tasian culture group is notable for producing the earliest blacktop-ware, a type of red and brown pottery which has been painted black on its top and interior.[3]

The Badarian Culture, named for the Badari site near Der Tasa, followed the Tasian culture, however similarities between the two have led many to avoid differentiating between them at all. The Badarian Culture continued to produce the kind of pottery called Blacktop-ware (although its quality was much improved over previous specimens), and was assigned the Sequence Dating numbers between 21 and 29.[4] The significant difference, however, between the Tasian and Badarian culture groups which prevents scholars from completely merging the two together is that Badarian sites use copper in addition to stone, and thus are chalcolithic settlements, while the Tasian sites are still Neolithic, and are considered technically part of the Stone Age.[4]

The Amratian culture is named after the site of el-Amra, about 120 km south of Badari. El-Amra was the first site where this culture group was found unmingled with the later Gerzean culture group; however, this period is better attested at the Naqada site, thus it is also referred to as the Naqada I culture.[5] Black-topped ware continued to be produced, but white cross-line ware, a type of pottery which was decorated with close parallel white lines crossed by another set of close parallel white lines, began to be produced during this time. The Amratian period falls between S.D. 30 and 39 in Petrie's Sequence Dating system.[6] Trade between Upper and Lower Egypt was attested at this time, as newly excavated objects indicate. A stone vase from the north was found at el-Amra, and copper, which is not present in Egypt, was apparently imported from the Sinai, or perhaps from Nubia. Obsidian[7] and an extremely small amount of gold[6] were both definitively imported from Nubia during this time. Trade with the oases was also likely.[7]

The Gerzean Culture, named after the site of Gerza, was the next stage in Egyptian cultural development, and it was during this time that the foundation for Dynastic Egypt was laid. Gerzean culture was largely an unbroken development out of Amratian Culture, starting in the delta and moving south through upper Egypt; however, it failed to dislodge Amratian Culture in Nubia.[8] Gerzean culture coincided with a significant drop in rainfall,[8] and farming produced the vast majority of food.[8] With increased food supplies, the populace adopted a much more sedentary lifestyle, and the larger settlements grew to cities of about 5,000 residents.[8] It was in this time that the city dwellers started using mud brick to build their cities.[8] Copper instead of stone was increasingly used to make tools[8] and weaponry.[9] Silver, gold, lapis, and faience were used ornamentally,[10] and the grinding palettes used for eye-paint since the Badarian period began to be adorned with relief carvings.

Along the Nile, in the 12th millennium BC, a grain-grinding culture using the earliest type of sickle blades had been replaced by another culture of hunters, fishers, and gathering people using stone tools. Evidence also indicates human habitation and cattle herding in the southwestern corner of Egypt, near the Sudan border, before 8000 BC. Geological evidence and computer climate modeling studies suggest that natural climate changes around 8000 BC began to desiccate the extensive pastoral lands of northern Africa, eventually forming the Sahara (c.2500 BC). Early tribes in the region naturally tended to aggregate close to the Nile River where they developed a settled agricultural economy and more centralized society. There is evidence of pastoralism and cultivation of cereals in the East Sahara in the 7th millennium BC.

Continued desiccation forced the early ancestors of the Egyptians to settle around the Nile more permanently and forced them to adopt a more sedentary lifestyle. However, the period from 9000 to 6000 BC has left very little in the way of archaeological evidence.

Predynastic period

Main article: Predynastic Egypt

Further information: Naqada

A Naqada II vase decorated with gazelles, on display at the Louvre.

By about 6000 BC, organized agriculture and large building construction had appeared in the Nile Valley.[1] At this time, Egyptians in the southwestern corner of Egypt were herding cattle and also constructing large buildings. Mortar was in use by 4000 BC. The Predynastic Period continues through this time, variously held to begin with the Naqada culture.

Between 5500 and 3100 BC, during Egypt's Predynastic Period, small settlements flourished along the Nile, whose delta empties into the Mediterranean Sea. By 3300 BC, just before the first Egyptian dynasty, Egypt was divided into two kingdoms, known as Upper Egypt, Ta Shemau, to the south, and Lower Egypt, Ta Mehu, to the north.[2] The dividing line was drawn roughly in the area of modern Cairo.

The Tasian culture was the next to appear in Upper Egypt. This group is named for the burials found at Der Tasa, a site on the east bank of the Nile between Asyut and Akhmim. The Tasian culture group is notable for producing the earliest blacktop-ware, a type of red and brown pottery which has been painted black on its top and interior.[3]

The Badarian Culture, named for the Badari site near Der Tasa, followed the Tasian culture, however similarities between the two have led many to avoid differentiating between them at all. The Badarian Culture continued to produce the kind of pottery called Blacktop-ware (although its quality was much improved over previous specimens), and was assigned the Sequence Dating numbers between 21 and 29.[4] The significant difference, however, between the Tasian and Badarian culture groups which prevents scholars from completely merging the two together is that Badarian sites use copper in addition to stone, and thus are chalcolithic settlements, while the Tasian sites are still Neolithic, and are considered technically part of the Stone Age.[4]

The Amratian culture is named after the site of el-Amra, about 120 km south of Badari. El-Amra was the first site where this culture group was found unmingled with the later Gerzean culture group; however, this period is better attested at the Naqada site, thus it is also referred to as the Naqada I culture.[5] Black-topped ware continued to be produced, but white cross-line ware, a type of pottery which was decorated with close parallel white lines crossed by another set of close parallel white lines, began to be produced during this time. The Amratian period falls between S.D. 30 and 39 in Petrie's Sequence Dating system.[6] Trade between Upper and Lower Egypt was attested at this time, as newly excavated objects indicate. A stone vase from the north was found at el-Amra, and copper, which is not present in Egypt, was apparently imported from the Sinai, or perhaps from Nubia. Obsidian[7] and an extremely small amount of gold[6] were both definitively imported from Nubia during this time. Trade with the oases was also likely.[7]

The Gerzean Culture, named after the site of Gerza, was the next stage in Egyptian cultural development, and it was during this time that the foundation for Dynastic Egypt was laid. Gerzean culture was largely an unbroken development out of Amratian Culture, starting in the delta and moving south through upper Egypt; however, it failed to dislodge Amratian Culture in Nubia.[8] Gerzean culture coincided with a significant drop in rainfall,[8] and farming produced the vast majority of food.[8] With increased food supplies, the populace adopted a much more sedentary lifestyle, and the larger settlements grew to cities of about 5,000 residents.[8] It was in this time that the city dwellers started using mud brick to build their cities.[8] Copper instead of stone was increasingly used to make tools[8] and weaponry.[9] Silver, gold, lapis, and faience were used ornamentally,[10] and the grinding palettes used for eye-paint since the Badarian period began to be adorned with relief carvings.

Monday, July 11, 2011

St. Basil's Cathedral

The Cathedral of the Protection of Most Holy Theotokos on the Moat (Russian: Собор Покрова пресвятой Богородицы, что на Рву), popularly known as Saint Basil's Cathedral (Russian: Собор Василия Блаженного), is a Russian Orthodox church erected on the Red Square in Moscow in 1555–61. Built on the order of Ivan IV of Russia to commemorate the capture of Kazan and Astrakhan, it marks the geometric center of the city and the hub of its growth since the 14th century.[1][2] It was the tallest building in Moscow until the completion of the Ivan the Great Bell Tower in 1600.[3]

The original building, known as "Trinity Church" and later "Trinity Cathedral", contained eight side churches arranged around the ninth, central church of Intercession; the tenth church was erected in 1588 over the grave of venerated local saint Vasily (Basil). In the 16th and the 17th centuries the church, perceived as the earthly symbol of the Heavenly City,[4] was popularly known as the "Jerusalem" and served as an allegory of the Jerusalem Temple in the annual Palm Sunday parade attended by the Patriarch of Moscow and the tsar.[5]

The building's design, shaped as a flame of a bonfire rising into the sky,[6] has no analogues in Russian architecture: "It is like no other Russian building. Nothing similar can be found in the entire millennium of Byzantine tradition from the fifth to fifteenth century ... a strangeness that astonishes by its unexpectedness, complexity and dazzling interleaving of the manifold details of its design."[7] The cathedral foreshadowed the climax of Russian national architecture in the 17th century.[8]

The church has operated as a division of the State Historical Museum since 1928.[9] It was completely secularized in 1929[9] and, as of 2011, remains a federal property of the Russian Federation. The church has been part of the Moscow Kremlin and Red Square UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1990.[10]

It is often mislabeled as the Kremlin due to its location on Red Square in immediate proximity of the Kremlin.

The original building, known as "Trinity Church" and later "Trinity Cathedral", contained eight side churches arranged around the ninth, central church of Intercession; the tenth church was erected in 1588 over the grave of venerated local saint Vasily (Basil). In the 16th and the 17th centuries the church, perceived as the earthly symbol of the Heavenly City,[4] was popularly known as the "Jerusalem" and served as an allegory of the Jerusalem Temple in the annual Palm Sunday parade attended by the Patriarch of Moscow and the tsar.[5]

The building's design, shaped as a flame of a bonfire rising into the sky,[6] has no analogues in Russian architecture: "It is like no other Russian building. Nothing similar can be found in the entire millennium of Byzantine tradition from the fifth to fifteenth century ... a strangeness that astonishes by its unexpectedness, complexity and dazzling interleaving of the manifold details of its design."[7] The cathedral foreshadowed the climax of Russian national architecture in the 17th century.[8]

The church has operated as a division of the State Historical Museum since 1928.[9] It was completely secularized in 1929[9] and, as of 2011, remains a federal property of the Russian Federation. The church has been part of the Moscow Kremlin and Red Square UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1990.[10]

It is often mislabeled as the Kremlin due to its location on Red Square in immediate proximity of the Kremlin.

Sunday, July 10, 2011

Air Pollution

Air is the ocean we breathe. Air supplies us with oxygen which is essential for our bodies to live. Air is 99.9% nitrogen, oxygen, water vapor and inert gases. Human activities can release substances into the air, some of which can cause problems for humans, plants, and animals.

There are several main types of pollution and well-known effects of pollution which are commonly discussed. These include smog, acid rain, the greenhouse effect, and "holes" in the ozone layer. Each of these problems has serious implications for our health and well-being as well as for the whole environment.

One type of air pollution is the release of particles into the air from burning fuel for energy. Diesel smoke is a good example of this particulate matter . The particles are very small pieces of matter measuring about 2.5 microns or about .0001 inches. This type of pollution is sometimes referred to as "black carbon" pollution. The exhaust from burning fuels in automobiles, homes, and industries is a major source of pollution in the air. Some authorities believe that even the burning of wood and charcoal in fireplaces and barbeques can release significant quanitites of soot into the air.

Another type of pollution is the release of noxious gases, such as sulfur dioxide, carbon monoxide, nitrogen oxides, and chemical vapors. These can take part in further chemical reactions once they are in the atmosphere, forming smog and acid rain.

Pollution also needs to be considered inside our homes, offices, and schools. Some of these pollutants can be created by indoor activities such as smoking and cooking. In the United States, we spend about 80-90% of our time inside buildings, and so our exposure to harmful indoor pollutants can be serious. It is therefore important to consider both indoor and outdoor air pollution.

There are several main types of pollution and well-known effects of pollution which are commonly discussed. These include smog, acid rain, the greenhouse effect, and "holes" in the ozone layer. Each of these problems has serious implications for our health and well-being as well as for the whole environment.

One type of air pollution is the release of particles into the air from burning fuel for energy. Diesel smoke is a good example of this particulate matter . The particles are very small pieces of matter measuring about 2.5 microns or about .0001 inches. This type of pollution is sometimes referred to as "black carbon" pollution. The exhaust from burning fuels in automobiles, homes, and industries is a major source of pollution in the air. Some authorities believe that even the burning of wood and charcoal in fireplaces and barbeques can release significant quanitites of soot into the air.

Another type of pollution is the release of noxious gases, such as sulfur dioxide, carbon monoxide, nitrogen oxides, and chemical vapors. These can take part in further chemical reactions once they are in the atmosphere, forming smog and acid rain.

Pollution also needs to be considered inside our homes, offices, and schools. Some of these pollutants can be created by indoor activities such as smoking and cooking. In the United States, we spend about 80-90% of our time inside buildings, and so our exposure to harmful indoor pollutants can be serious. It is therefore important to consider both indoor and outdoor air pollution.

Saturday, July 9, 2011

History of Polo

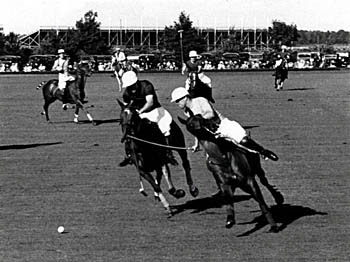

Polo is arguably the oldest recorded team sport in known history, with the first matches being played in Persia over 2500 years ago. Initially thought to have been created by competing tribes of Central Asia, it was quickly taken up as a training method for the King’s elite cavalry. These matches could resemble a battle with up to 100 men to a side.

As mounted armies swept back and forth across this part of the world, conquering and re-conquering, polo was adopted as the most noble of pastimes by the Kings and Emperors, Shahs and Sultans, Khans and Caliphs of the ancient Persians, Arabs, Mughals, Mongols and Chinese. It was for this reason it became known across the lands as "the game of kings".

British officers themselves re-invented the game in 1862 after seeing a horsemanship exhibition in Manipur, India. The sport was introduced into England in 1869, and seven years later sportsman James Gordon Bennett imported it to the United States. After 1886, English and American teams occasionally met for the International Polo Challenge Cup. Polo was on several Olympic games schedules, but was last an Olympic sport in 1936.

Polo continues, as it has done for so long, to represent the pinnacle of sport, and reaffirms the special bond between horse and rider. The feeling of many of its players are epitomized by a famous verse inscribed on a stone tablet next to a polo ground in Gilgit, Pakistan: "Let others play at other things. The king of games is still the game of kings."

Source: pro-polo.com

Quote from Xenophon

POLO FACTS

· The Basics: Polo is a ball sport, played on horses. Where one team attempts to score goals by hitting hard hockey-sized ball through their oppositions' goal with a mallet attached to the end of a 4 1/4 foot stick.

· The Pitch: The outdoor polo field is 300 yards long and 160 yards wide, the largest field in organized sport. The goal posts at each end are 24 feet apart and a minimum of 10 feet high. Penalty lines are marked at 30 yards from the goal, 40 yards, 60 yards, and at midfield.

· Chukkas: Each polo match is divided in to "Chukkas". A chukka is 7 1/2 minutes of active play time and is supposed to represent the amount of time a horse can reasonably exert itself before needing a rest. Polo Matches are divided into 4,5, or 6 Chukkas depending whether the level is Low, Medium, or High goal polo.

· Players: In outdoor polo there is four players on a team. Numbers 1 - 2 are traditionally attacking whilst 3 is the midfield playmaker and 4 is Defense. However as the sport is so fluid there are no definite positions in Polo.

· Handicaps: Handicaps in Polo range from -2 to 10 "goals". With 10 being the best. A player who is playing above his handicap level (i.e. 3 playing as a 5) is known as a bandit, and is a very valuable but short lived commodity. Handicaps are assessed and independently mediated several times during the season.

· Umpires: Two mounted umpires, referee the game. They must agree on each foul/call made, if they disagree they refer to the "3rd Man" who would be on the edge of the pitch in line with the center mark. His decision will settle the argument.

· The Rules: The Rules of polo are centered almost in totality around safety. When you have 1/2 a ton of horse traveling one way in excess of 30mph, you do not want to be hit by 1/2 a ton of horse traveling in excess of 30 mph the other way. Polo is inherently dangerous, which may be part of the allure; however, the rules go a long way to negate risk.

MORE POLO HISTORY...

"The King of Games" - Let other people play at other things. The King of Games is still the Game of Kings.

This verse, inscribed on a stone tablet beside a polo ground South of the fables silk route from China to the West, sums up the ancient history of what is believed to be the oldest organized sport in the world. Polo was truly a game of Kings, for most of its reputed 2,500 years or more of existence. Although the precise origin of polo is obscure and undocumented, there is ample evidence of the game's regal place in the history of Asia. No one knows where or when stick first met ball after the horse was domesticated by the tribes of Central Asia, but it seems likely that as the use of light cavalry spread throughout Asia Minor, China and the Indian sub-continent so did this rugged game on horse back. As mounted Armies swept back and forth across this part of the world, conquering and re-conquering, polo was adopted as the most noble of pastimes by the Kings and Emperors, Shahs and Sultans, Khans and Caliphs of the ancient Persians, Arabs, Mughals, Mongols and Chinese. The great rulers and their horsemen real and legendary, of those early centuries were expected to be brave warriors, skillful hunters and polo players of exceptional prowess.

Some scholars believe that polo originated among the Iranian tribes sometime before Darius-I and his cavalry forged the first great Persian Empire in the 6th century B.C. Certainly it is Persian literature and art which give us the richest accounts of polo in antiquity. Firdausi, the most famous of Persia’s poet-historian, gives a number of accounts of royal polo tournaments in his 9th century epic, Shahnamah. Some believe that the Chinese (the Mongols) were the first to try their hands at the game. In the earliest account, Firdausi romanticizes an international match between Turanian force and the followers of Syavoush, a legendary Persian ruler from the earliest centuries of the Empire. The poet is eloquent in his praise of Syavoush's skills on the polo field. Firdausi also tells of Sapor-II Sassanid, King of the 4th Century A.D., who learn to play polo when he was only seven years old. Another 9th century historian, Dinvari, describes polo and its general rules and gives some instructions to players including such advice as 'polo requires a great deal of exercise’, ‘if polo stick breaks during a game it is a sign of inefficiency' and 'a player should strictly avoid using strong language and should be patient and temperate'. During the 10th century the Persian King Qabus also set down some general rules of polo and especially mentioned the risks and dangers of the game.

The 13th century poet Nizami weaves the love story of the Sassanid King Khusru and his beautiful consort Shirin, around her ability on the polo field, and describes matches between Khusru and his courtiers and Shirin and her ladies-in-waiting. Nurjehan, wife of the 19th century Mughal Emperor Jahangir, was also skilled at polo. Polo was a popular royal pastime for many centuries in China, the Chinese probably having learned the game from the same Indian tribes who were taught by the Persians. The polo stick appears on royal coats of arms in China and the game was part of the court life in the golden age of Chinese classical culture under Ming-Hung, the Radiant Emperor, who as an enthusiastic patron of equestrian activities. Less cultured, one might think, was the reaction of Emperor Tai Tsu in 9 10 A.D. who according to one source, ordered all the other players beheaded after a favorite was killed in a match.

Several controversies still run rampant over the exact origins of polo. Depending on what country you are in the exact history of polo can vary. However, some parts of the history do remain the same.

POLO - The oldest team sport, the exact origin of polo is unknown. Polo was probably first played by nomadic warriors over two thousand years ago. Used for training cavalry, the game was played from Constantinople to Japan in the Middle Ages. Tamerlane's polo grounds can still be seen in Samarkand. British tea planters in India first saw the game in the early 1800's. However, it was not until the 1850's that the British cavalry drew up the first rules and by the 1870's, the game was well established in England.

James Gordon Bennett, a noted American publisher, brought polo to New York in 1876. Within ten years, there were major clubs all over the east including Long Island.

Over the next 50 years, polo achieved tremendous popularity in the United States. By the 1930's, polo was an Olympic sport and crowds in excess of 30,000 regularly attended international matches at the Meadow Brook Polo Club on Long Island.

In the 1950's, intercollegiate polo was played by only four teams. Today, it includes more than 25 colleges and universities. Player membership in the United States Polo Association has more than tripled with over 250 active clubs, with almost 1000 polo clubs worldwide in almost every country on the globe.

As mounted armies swept back and forth across this part of the world, conquering and re-conquering, polo was adopted as the most noble of pastimes by the Kings and Emperors, Shahs and Sultans, Khans and Caliphs of the ancient Persians, Arabs, Mughals, Mongols and Chinese. It was for this reason it became known across the lands as "the game of kings".

British officers themselves re-invented the game in 1862 after seeing a horsemanship exhibition in Manipur, India. The sport was introduced into England in 1869, and seven years later sportsman James Gordon Bennett imported it to the United States. After 1886, English and American teams occasionally met for the International Polo Challenge Cup. Polo was on several Olympic games schedules, but was last an Olympic sport in 1936.

Polo continues, as it has done for so long, to represent the pinnacle of sport, and reaffirms the special bond between horse and rider. The feeling of many of its players are epitomized by a famous verse inscribed on a stone tablet next to a polo ground in Gilgit, Pakistan: "Let others play at other things. The king of games is still the game of kings."

Source: pro-polo.com

Quote from Xenophon

POLO FACTS

· The Basics: Polo is a ball sport, played on horses. Where one team attempts to score goals by hitting hard hockey-sized ball through their oppositions' goal with a mallet attached to the end of a 4 1/4 foot stick.

· The Pitch: The outdoor polo field is 300 yards long and 160 yards wide, the largest field in organized sport. The goal posts at each end are 24 feet apart and a minimum of 10 feet high. Penalty lines are marked at 30 yards from the goal, 40 yards, 60 yards, and at midfield.

· Chukkas: Each polo match is divided in to "Chukkas". A chukka is 7 1/2 minutes of active play time and is supposed to represent the amount of time a horse can reasonably exert itself before needing a rest. Polo Matches are divided into 4,5, or 6 Chukkas depending whether the level is Low, Medium, or High goal polo.

· Players: In outdoor polo there is four players on a team. Numbers 1 - 2 are traditionally attacking whilst 3 is the midfield playmaker and 4 is Defense. However as the sport is so fluid there are no definite positions in Polo.

· Handicaps: Handicaps in Polo range from -2 to 10 "goals". With 10 being the best. A player who is playing above his handicap level (i.e. 3 playing as a 5) is known as a bandit, and is a very valuable but short lived commodity. Handicaps are assessed and independently mediated several times during the season.

· Umpires: Two mounted umpires, referee the game. They must agree on each foul/call made, if they disagree they refer to the "3rd Man" who would be on the edge of the pitch in line with the center mark. His decision will settle the argument.

· The Rules: The Rules of polo are centered almost in totality around safety. When you have 1/2 a ton of horse traveling one way in excess of 30mph, you do not want to be hit by 1/2 a ton of horse traveling in excess of 30 mph the other way. Polo is inherently dangerous, which may be part of the allure; however, the rules go a long way to negate risk.

MORE POLO HISTORY...

"The King of Games" - Let other people play at other things. The King of Games is still the Game of Kings.

This verse, inscribed on a stone tablet beside a polo ground South of the fables silk route from China to the West, sums up the ancient history of what is believed to be the oldest organized sport in the world. Polo was truly a game of Kings, for most of its reputed 2,500 years or more of existence. Although the precise origin of polo is obscure and undocumented, there is ample evidence of the game's regal place in the history of Asia. No one knows where or when stick first met ball after the horse was domesticated by the tribes of Central Asia, but it seems likely that as the use of light cavalry spread throughout Asia Minor, China and the Indian sub-continent so did this rugged game on horse back. As mounted Armies swept back and forth across this part of the world, conquering and re-conquering, polo was adopted as the most noble of pastimes by the Kings and Emperors, Shahs and Sultans, Khans and Caliphs of the ancient Persians, Arabs, Mughals, Mongols and Chinese. The great rulers and their horsemen real and legendary, of those early centuries were expected to be brave warriors, skillful hunters and polo players of exceptional prowess.

Some scholars believe that polo originated among the Iranian tribes sometime before Darius-I and his cavalry forged the first great Persian Empire in the 6th century B.C. Certainly it is Persian literature and art which give us the richest accounts of polo in antiquity. Firdausi, the most famous of Persia’s poet-historian, gives a number of accounts of royal polo tournaments in his 9th century epic, Shahnamah. Some believe that the Chinese (the Mongols) were the first to try their hands at the game. In the earliest account, Firdausi romanticizes an international match between Turanian force and the followers of Syavoush, a legendary Persian ruler from the earliest centuries of the Empire. The poet is eloquent in his praise of Syavoush's skills on the polo field. Firdausi also tells of Sapor-II Sassanid, King of the 4th Century A.D., who learn to play polo when he was only seven years old. Another 9th century historian, Dinvari, describes polo and its general rules and gives some instructions to players including such advice as 'polo requires a great deal of exercise’, ‘if polo stick breaks during a game it is a sign of inefficiency' and 'a player should strictly avoid using strong language and should be patient and temperate'. During the 10th century the Persian King Qabus also set down some general rules of polo and especially mentioned the risks and dangers of the game.

The 13th century poet Nizami weaves the love story of the Sassanid King Khusru and his beautiful consort Shirin, around her ability on the polo field, and describes matches between Khusru and his courtiers and Shirin and her ladies-in-waiting. Nurjehan, wife of the 19th century Mughal Emperor Jahangir, was also skilled at polo. Polo was a popular royal pastime for many centuries in China, the Chinese probably having learned the game from the same Indian tribes who were taught by the Persians. The polo stick appears on royal coats of arms in China and the game was part of the court life in the golden age of Chinese classical culture under Ming-Hung, the Radiant Emperor, who as an enthusiastic patron of equestrian activities. Less cultured, one might think, was the reaction of Emperor Tai Tsu in 9 10 A.D. who according to one source, ordered all the other players beheaded after a favorite was killed in a match.

Several controversies still run rampant over the exact origins of polo. Depending on what country you are in the exact history of polo can vary. However, some parts of the history do remain the same.

POLO - The oldest team sport, the exact origin of polo is unknown. Polo was probably first played by nomadic warriors over two thousand years ago. Used for training cavalry, the game was played from Constantinople to Japan in the Middle Ages. Tamerlane's polo grounds can still be seen in Samarkand. British tea planters in India first saw the game in the early 1800's. However, it was not until the 1850's that the British cavalry drew up the first rules and by the 1870's, the game was well established in England.

James Gordon Bennett, a noted American publisher, brought polo to New York in 1876. Within ten years, there were major clubs all over the east including Long Island.

Over the next 50 years, polo achieved tremendous popularity in the United States. By the 1930's, polo was an Olympic sport and crowds in excess of 30,000 regularly attended international matches at the Meadow Brook Polo Club on Long Island.

In the 1950's, intercollegiate polo was played by only four teams. Today, it includes more than 25 colleges and universities. Player membership in the United States Polo Association has more than tripled with over 250 active clubs, with almost 1000 polo clubs worldwide in almost every country on the globe.

Friday, July 8, 2011

History of Oxford University

History’ at Oxford encompasses the history of the wider European and Mediterranean world since circa 300 AD, and of most of the rest of the world from the early modern period. Some of the topics included within it border on other fields of study:

Economic and Social History

History of Science and Medicine

History of Art.

In that context, History recruits some students and borrows some staff from other disciplinary backgrounds. The Faculty administers and contributes to the teaching of some explicitly interdisciplinary Master’s programmes: in Late Antique and Byzantine Studies and Medieval Studies.

Research Programmes

Humanities Division

DPhil and MLitt in History

Course Code | 000871

DPhil and MLitt in History (History of Science and Medicine & Economics and Social History)

Course Code | 003950

The whole range of the Faculty's research interests is covered including History of Science, History of Medicine, History of Art and Economic History. The DPhil entails the writing of a thesis of up to 100,000 words which may involve either the finding of new or re-examination of known sources.

The MLitt involves writing a thesis of up to 50,000 words which is usually based on original sources, printed or manuscript. Further details of these programmes are available from the departmental website.

During the first one or two years candidates for either degree pursue a mixed course of skills training (palaeography, statistics etc. as appropriate), seminars and paper writing, while preparing a detailed outline of their thesis under the guidance of a supervisor. They may be required to attend certain classes provided for the various taught graduate programmes described below.

How to Apply

The deadline for the DPhil in History are 19 November 2010 and 21 January 2011. The deadlines for the DPhil in History (History of Science and Medicine, Economic and Social History) are 19 November 2010, 21 January 2011 and 11 March 2011.

All those seeking funding from Research Council, University, Faculty, or Faculty-College linked resources must apply by 21 January 2011.

The standard set of materials you should send with any application to a research course comprises:

A research proposal,

CV/résumé,

Three (3) academic references, and

Official transcripts detailing your university-level qualifications and marks to date.

In addition to the standard documents above, applicants to all DPhil programmes in History should provide two (2) relevant academic essays or other writing samples from their most recent qualification of 2,000 words each, or 2,000-word extracts of longer work.

The research proposal for applicants to all DPhil programmes in History is expected to supply your research question, discuss its historiographical context, give an indication of the kinds of sources you have identified and expect to use, and outline your methodological approach to dealing with the sources and constructing your thesis.

Please follow the detailed instructions in the Application Guide, and consult the History website for any additional guidance.

Back to top

Taught Programmes

Humanities Division

The Master’s programmes offered by the History Faculty provide an entry route into Oxford research degrees, but may also function as free-standing programmes of study. They provide a grounding in research methods in some given field of historical knowledge. Taught programmes last for 9, 11 and 12 months (for MSts, MScs) and 21 months (for MPhils). Students completing the substantial dissertation required for an MPhil may apply for readmission to the DPhil programme and develop their MPhil thesis into a doctoral thesis by extending their primary research base in an additional one or two years.

MSt in Medieval History

Course Code | 003780

This programme provides the normal entry route to research degrees for all medieval historians not already holding relevant Master’s degrees, or seeking qualification through an interdisciplinary programme such as the MSt or MPhil in Late Antique and Byzantine Studies or MSt in Medieval Studies. It balances taught classes, language training and independent research. Oxford’s strength in medieval history means that almost any area of medieval European history can be studied. Language training is available in Latin, most modern languages, medieval languages (including Celtic, Romance and Germanic languages), and Greek.

The taught classes consist of a core course in the first term focusing on historical methods, and a choice of optional subjects in the second term, with a chronological spread across the Middle Ages. Candidates will also work towards a dissertation of up to 15,000 words which is to be submitted in August.

Length of programme: Eleven months

For a list of core and optional courses, see the departmental website.

MSt in Modern British & European History

Course Code | 000893

This Master’s programme meets the needs of students seeking

the experience of graduate study and research in post-medieval

history of the area, including those wishing to prepare themselves for doctoral work.

Research training in historical theory, methods, sources and resources is combined with the focussed study of options which showcase recent historiography and approaches.

This class work parallels supervised pursuit of a research project. Candidates will work towards a dissertation of up to 15,000 words which is to be submitted for examination in late May.

Length of programme: Nine months

For a list of core and optional courses, see the departmental website

MSt in Global and Imperial History

Course Code | 000892

This programme meets the needs of students seeking the experience of graduate study and research in either Commonwealth and Imperial, or South Asian, or East Asian history, including those wishing to prepare themselves for doctoral work. In each stream, research training is combined with broad conceptual approaches that encourage students to learn from the recent historiographies of different periods and areas and with focused studies of periods or themes. This class work parallels supervised pursuit of a research project. Candidates will work towards a dissertation of up to 15,000 words which is to be submitted for examination in late May.

Length of programme: Nine months

For a list of core and optional courses, see the departmental website

MSt in US History

Course Code | 000894

This programme meets the needs of students seeking the experience of graduate study and research in the history of the United States and its colonial antecedents, including those wishing to prepare themselves for doctoral work in this field.

Students receive training in methods and evidence in the history of the United States of America and study US historiography and contemporary historical debates. Teaching is through participation in classes and research seminars, enhanced by tutorial sessions.

This class work parallels supervised pursuit of a research project. Candidates will work towards a dissertation of up to 15,000 words which is to be submitted for examination in late May.

Length of programme: Nine months

For a list of core and optional courses, see the departmental website

MPhil in Modern British and European History

Course Code | 000895

The joint initial theoretical and methodological training with the MSt in Modern British and European History is enhanced for this degree by a class on the contemporary writing of history. In addition students expand their contextual understanding by choosing from a menu of thematic options which showcase recent historiography and approaches.

The summer vacation and second Michaelmas Term are set aside for individual research which will feed into work towards the completion of a substantial dissertation of up to 30,000 words which in many cases may form the basis of a doctoral project.

The writing up of the dissertation during the second half of the second year is supported by a master class in which students have the opportunity to address wider historiographical, theoretical and methodological issues through the medium of their own research.

Length of programme: Twenty-one months

For a list of core and optional courses, see the departmental website

MPhil in Economic and Social History

Course Code | 000570

This degree programme is designed both to educate historians in the methods of social science research, and to expose students with social science backgrounds to the challenges of historical enquiry.

It offers, in addition to economic and social history in the strict sense, a choice of papers covering the history of science and technology, the social history of medicine and historical demography.

Students do two core papers on the methodologies of economic and social history and four advanced papers, selected from a wide range of options, which may include up to two papers in a related discipline or skill (such as Economics or Sociology).

In parallel they will work towards the completion of a substantial dissertation of up to 30,000 words which in many cases may form the basis of a doctoral project.

Length of programme: Twenty-one months

For a list of core and optional courses, see the departmental website

MSc in Economic and Social History

Course Code | 000580

This degree programme is a more concise version of the parent MPhil, and provides the usual entry route into research for candidates who seek funding from the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) in the field of Economic and Social History.

Students do two core papers on the methodologies of economic and social history and two advanced papers, selected from a wide range of options, which may include one paper in a related discipline or skill (such as Economics or Sociology).

Candidates will also work towards a dissertation of up to 15,000 words which is to be submitted in September.

Length of programme: Twelve months

For a list of core and optional courses, see the departmental website

MPhil in History of Science, Medicine, and Technology

Course Code | 000740

This degree programme is designed to enhance history students’ knowledge and understanding of the history of science and medicine, and to enhance the historical knowledge and understanding of students with mainly science backgrounds.

It shares many resources with its sister programmes in economic and social history. It provides in-depth training in the methods and themes of the history of science and technology and the social history of medicine.

Students will be examined in four papers, which may comprise either four Advanced Papers focusing on particular periods and topics, or three Advanced Papers, and one paper in a related discipline or skill (such as Comparative Social Policy).

In parallel they will work towards the completion of a substantial dissertation of up to 30,000 words which in many cases may form the basis of a doctoral project.

Length of programme: Twenty-one months

For a list of core and optional courses, see the departmental website

Economic and Social History

History of Science and Medicine

History of Art.

In that context, History recruits some students and borrows some staff from other disciplinary backgrounds. The Faculty administers and contributes to the teaching of some explicitly interdisciplinary Master’s programmes: in Late Antique and Byzantine Studies and Medieval Studies.

Research Programmes

Humanities Division

DPhil and MLitt in History

Course Code | 000871

DPhil and MLitt in History (History of Science and Medicine & Economics and Social History)

Course Code | 003950

The whole range of the Faculty's research interests is covered including History of Science, History of Medicine, History of Art and Economic History. The DPhil entails the writing of a thesis of up to 100,000 words which may involve either the finding of new or re-examination of known sources.

The MLitt involves writing a thesis of up to 50,000 words which is usually based on original sources, printed or manuscript. Further details of these programmes are available from the departmental website.

During the first one or two years candidates for either degree pursue a mixed course of skills training (palaeography, statistics etc. as appropriate), seminars and paper writing, while preparing a detailed outline of their thesis under the guidance of a supervisor. They may be required to attend certain classes provided for the various taught graduate programmes described below.

How to Apply

The deadline for the DPhil in History are 19 November 2010 and 21 January 2011. The deadlines for the DPhil in History (History of Science and Medicine, Economic and Social History) are 19 November 2010, 21 January 2011 and 11 March 2011.

All those seeking funding from Research Council, University, Faculty, or Faculty-College linked resources must apply by 21 January 2011.

The standard set of materials you should send with any application to a research course comprises:

A research proposal,

CV/résumé,

Three (3) academic references, and

Official transcripts detailing your university-level qualifications and marks to date.

In addition to the standard documents above, applicants to all DPhil programmes in History should provide two (2) relevant academic essays or other writing samples from their most recent qualification of 2,000 words each, or 2,000-word extracts of longer work.

The research proposal for applicants to all DPhil programmes in History is expected to supply your research question, discuss its historiographical context, give an indication of the kinds of sources you have identified and expect to use, and outline your methodological approach to dealing with the sources and constructing your thesis.

Please follow the detailed instructions in the Application Guide, and consult the History website for any additional guidance.

Back to top

Taught Programmes

Humanities Division

The Master’s programmes offered by the History Faculty provide an entry route into Oxford research degrees, but may also function as free-standing programmes of study. They provide a grounding in research methods in some given field of historical knowledge. Taught programmes last for 9, 11 and 12 months (for MSts, MScs) and 21 months (for MPhils). Students completing the substantial dissertation required for an MPhil may apply for readmission to the DPhil programme and develop their MPhil thesis into a doctoral thesis by extending their primary research base in an additional one or two years.

MSt in Medieval History

Course Code | 003780

This programme provides the normal entry route to research degrees for all medieval historians not already holding relevant Master’s degrees, or seeking qualification through an interdisciplinary programme such as the MSt or MPhil in Late Antique and Byzantine Studies or MSt in Medieval Studies. It balances taught classes, language training and independent research. Oxford’s strength in medieval history means that almost any area of medieval European history can be studied. Language training is available in Latin, most modern languages, medieval languages (including Celtic, Romance and Germanic languages), and Greek.

The taught classes consist of a core course in the first term focusing on historical methods, and a choice of optional subjects in the second term, with a chronological spread across the Middle Ages. Candidates will also work towards a dissertation of up to 15,000 words which is to be submitted in August.

Length of programme: Eleven months

For a list of core and optional courses, see the departmental website.

MSt in Modern British & European History

Course Code | 000893

This Master’s programme meets the needs of students seeking

the experience of graduate study and research in post-medieval

history of the area, including those wishing to prepare themselves for doctoral work.

Research training in historical theory, methods, sources and resources is combined with the focussed study of options which showcase recent historiography and approaches.

This class work parallels supervised pursuit of a research project. Candidates will work towards a dissertation of up to 15,000 words which is to be submitted for examination in late May.

Length of programme: Nine months

For a list of core and optional courses, see the departmental website

MSt in Global and Imperial History

Course Code | 000892

This programme meets the needs of students seeking the experience of graduate study and research in either Commonwealth and Imperial, or South Asian, or East Asian history, including those wishing to prepare themselves for doctoral work. In each stream, research training is combined with broad conceptual approaches that encourage students to learn from the recent historiographies of different periods and areas and with focused studies of periods or themes. This class work parallels supervised pursuit of a research project. Candidates will work towards a dissertation of up to 15,000 words which is to be submitted for examination in late May.

Length of programme: Nine months

For a list of core and optional courses, see the departmental website

MSt in US History

Course Code | 000894

This programme meets the needs of students seeking the experience of graduate study and research in the history of the United States and its colonial antecedents, including those wishing to prepare themselves for doctoral work in this field.

Students receive training in methods and evidence in the history of the United States of America and study US historiography and contemporary historical debates. Teaching is through participation in classes and research seminars, enhanced by tutorial sessions.

This class work parallels supervised pursuit of a research project. Candidates will work towards a dissertation of up to 15,000 words which is to be submitted for examination in late May.

Length of programme: Nine months

For a list of core and optional courses, see the departmental website

MPhil in Modern British and European History

Course Code | 000895

The joint initial theoretical and methodological training with the MSt in Modern British and European History is enhanced for this degree by a class on the contemporary writing of history. In addition students expand their contextual understanding by choosing from a menu of thematic options which showcase recent historiography and approaches.

The summer vacation and second Michaelmas Term are set aside for individual research which will feed into work towards the completion of a substantial dissertation of up to 30,000 words which in many cases may form the basis of a doctoral project.

The writing up of the dissertation during the second half of the second year is supported by a master class in which students have the opportunity to address wider historiographical, theoretical and methodological issues through the medium of their own research.

Length of programme: Twenty-one months

For a list of core and optional courses, see the departmental website

MPhil in Economic and Social History

Course Code | 000570

This degree programme is designed both to educate historians in the methods of social science research, and to expose students with social science backgrounds to the challenges of historical enquiry.

It offers, in addition to economic and social history in the strict sense, a choice of papers covering the history of science and technology, the social history of medicine and historical demography.

Students do two core papers on the methodologies of economic and social history and four advanced papers, selected from a wide range of options, which may include up to two papers in a related discipline or skill (such as Economics or Sociology).

In parallel they will work towards the completion of a substantial dissertation of up to 30,000 words which in many cases may form the basis of a doctoral project.

Length of programme: Twenty-one months

For a list of core and optional courses, see the departmental website

MSc in Economic and Social History

Course Code | 000580

This degree programme is a more concise version of the parent MPhil, and provides the usual entry route into research for candidates who seek funding from the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) in the field of Economic and Social History.

Students do two core papers on the methodologies of economic and social history and two advanced papers, selected from a wide range of options, which may include one paper in a related discipline or skill (such as Economics or Sociology).

Candidates will also work towards a dissertation of up to 15,000 words which is to be submitted in September.

Length of programme: Twelve months

For a list of core and optional courses, see the departmental website

MPhil in History of Science, Medicine, and Technology

Course Code | 000740

This degree programme is designed to enhance history students’ knowledge and understanding of the history of science and medicine, and to enhance the historical knowledge and understanding of students with mainly science backgrounds.

It shares many resources with its sister programmes in economic and social history. It provides in-depth training in the methods and themes of the history of science and technology and the social history of medicine.

Students will be examined in four papers, which may comprise either four Advanced Papers focusing on particular periods and topics, or three Advanced Papers, and one paper in a related discipline or skill (such as Comparative Social Policy).

In parallel they will work towards the completion of a substantial dissertation of up to 30,000 words which in many cases may form the basis of a doctoral project.

Length of programme: Twenty-one months

For a list of core and optional courses, see the departmental website

Wednesday, July 6, 2011

History of Jews

Early Christian thought held Jews collectively responsible for the crucifixion of Jesus. This religious teaching became embedded in both Catholic and Protestant theology during the first millennium, with terrible consequences for Jews. Following many centuries of persecution and exclusion, the Jewish minority in Europe achieved some rights after the Enlightenment. As Europe became more secular and Jews integrated into mainstream society, political forms of antisemitism emerged. Jews were targeted for their ideas and their role in society. In the late nineteenth century, pseudo-scientific theories that legitimized a racial form of antisemitism became popular with some intellectuals and political leaders. All of these centuries of hatred were exploited by the Nazis and their allies during World War II culminating in the Holocaust, the systematic murder of Europe’s Jews.

A woman sits on a park bench marked “Only for Jews.” Austria, ca. March 1938. —USHMM #11195/Institute of Contemporary History and Wiener Library Limited

In February 2007, a Jewish memorial to the Holocaust was defaced and nearly 300 Jewish graves desecrated in Odessa in southern Ukraine.

In February 2007, a Jewish memorial to the Holocaust was defaced and nearly 300 Jewish graves desecrated in Odessa in southern Ukraine. —Photo courtesy European Jewish Press

In recent years, there has been an increase in antisemitism, in the form of hate speech, violence, and denial of the Holocaust. These incidents are occurring everywhere, but especially in the Islamic world and in lands where the Holocaust occurred. In many Middle Eastern countries, antisemitism is promoted in state-controlled media and educational systems, and militant groups with political power, such as Hamas, use genocidal language regarding Jews and the State of Israel. The president of Iran repeatedly has declared the Holocaust a “myth” and that Israel should be “wiped off the map.” In Europe, antisemitism is increasingly evident among both far-right and far-left political parties. And in the United States, some Jewish students on some college campuses are confronted by antisemitic hostility. Violence targeting Jews and Jewish institutions continues around the world. Denial and minimization of the Holocaust, along with other forms of hatred against Jews, is now widespread on the Internet in multiple languages.

In the aftermath of the moral and societal failures that made the Holocaust possible, confronting antisemitism and all forms of hatred is critical.

A woman sits on a park bench marked “Only for Jews.” Austria, ca. March 1938. —USHMM #11195/Institute of Contemporary History and Wiener Library Limited

In February 2007, a Jewish memorial to the Holocaust was defaced and nearly 300 Jewish graves desecrated in Odessa in southern Ukraine.

In February 2007, a Jewish memorial to the Holocaust was defaced and nearly 300 Jewish graves desecrated in Odessa in southern Ukraine. —Photo courtesy European Jewish Press

In recent years, there has been an increase in antisemitism, in the form of hate speech, violence, and denial of the Holocaust. These incidents are occurring everywhere, but especially in the Islamic world and in lands where the Holocaust occurred. In many Middle Eastern countries, antisemitism is promoted in state-controlled media and educational systems, and militant groups with political power, such as Hamas, use genocidal language regarding Jews and the State of Israel. The president of Iran repeatedly has declared the Holocaust a “myth” and that Israel should be “wiped off the map.” In Europe, antisemitism is increasingly evident among both far-right and far-left political parties. And in the United States, some Jewish students on some college campuses are confronted by antisemitic hostility. Violence targeting Jews and Jewish institutions continues around the world. Denial and minimization of the Holocaust, along with other forms of hatred against Jews, is now widespread on the Internet in multiple languages.

In the aftermath of the moral and societal failures that made the Holocaust possible, confronting antisemitism and all forms of hatred is critical.

Saturday, July 2, 2011

History of FIFA

The Fédération Internationale de Football Association (FIFA) was founded in the rear of the headquarters of the Union Française de Sports Athlétiques at the Rue Saint Honoré 229 in Paris on 21 May 1904. The foundation act was signed by the authorised representatives of the following associations:

France - Union des Sociétés Françaises de Sports Athlétiques (USFSA)

Belgium - Union Belge des Sociétés de Sports (UBSSA)

Denmark - Dansk Boldspil Union (DBU)

Netherlands - Nederlandsche Voetbal Bond (NVB)

Spain - Madrid Football Club

Sweden - Svenska Bollspells Förbundet (SBF)

Switzerland - Association Suisse de Football (ASF)

Present at that historic meeting were: Robert Guérin and André Espir (France); Louis Muhlinghaus and Max Kahn (Belgium); Ludvig Sylow (Denmark); Carl Anton Wilhelm Hirschman (Netherlands); Victor E Schneider (Switzerland). Sylow also represented the SBF while Spir performed the same function for the Madrid Football Club.

When the idea of founding an international football federation began taking shape in Europe, the intention of those involved was to recognise the role of the English who had founded their Football Association back in 1863. Hirschman, secretary of the Netherlands Football Association, turned to the Football Association. Its secretary, FJ Wall, did accept the proposal but progress stalled while waiting for the Executive Committee of the Football Association, the International FA Board and the associations of Scotland, Wales and Ireland to give their opinion about the matter.

Guérin, secretary of the football department of the Union des Sociétés Françaises de Sports Athlétiques and a journalist with Le Matin newspaper, did not want to wait any longer. He contacted the national associations on the continent in writing and asked them to consider the possibility of founding an umbrella organisation.

When Belgium and France met in the first official international match in Brussels on 1 May 1904, Guérin discussed the subject with his Belgian counterpart Louis Muhlinghaus. It was now definite that the English FA, under its president Lord Kinnaird, would not be participating in the foundation of an international federation. So Guérin took the opportunity and sent out invitations to the founding assembly. The process of organising the international game had begun.

The first FIFA Statutes were laid down and the following points determined: the reciprocal and exclusive recognition of the national associations represented and attending; clubs and players were forbidden to play simultaneously for different national associations; recognition by the other associations of a player's suspension announced by an association; and the playing of matches according to the Laws of the Game of the Football Association Ltd.

Each national association had to pay an annual fee of FF50. Already then there were thoughts of staging an international competition and Article 9 stipulated that FIFA alone was entitled to take over the organisation of such an event. It was decided that these regulations would only come into force as of 1 September 1904. Moreover, the first Statutes of FIFA were only of a provisional nature, in order to simplify the acceptance of additional members. On the day of foundation, the Deutscher Fussball-Bund (German FA) sent a telegram confirming that it would adhere to these Statutes in principle.

France - Union des Sociétés Françaises de Sports Athlétiques (USFSA)

Belgium - Union Belge des Sociétés de Sports (UBSSA)

Denmark - Dansk Boldspil Union (DBU)

Netherlands - Nederlandsche Voetbal Bond (NVB)

Spain - Madrid Football Club

Sweden - Svenska Bollspells Förbundet (SBF)

Switzerland - Association Suisse de Football (ASF)

Present at that historic meeting were: Robert Guérin and André Espir (France); Louis Muhlinghaus and Max Kahn (Belgium); Ludvig Sylow (Denmark); Carl Anton Wilhelm Hirschman (Netherlands); Victor E Schneider (Switzerland). Sylow also represented the SBF while Spir performed the same function for the Madrid Football Club.

When the idea of founding an international football federation began taking shape in Europe, the intention of those involved was to recognise the role of the English who had founded their Football Association back in 1863. Hirschman, secretary of the Netherlands Football Association, turned to the Football Association. Its secretary, FJ Wall, did accept the proposal but progress stalled while waiting for the Executive Committee of the Football Association, the International FA Board and the associations of Scotland, Wales and Ireland to give their opinion about the matter.

Guérin, secretary of the football department of the Union des Sociétés Françaises de Sports Athlétiques and a journalist with Le Matin newspaper, did not want to wait any longer. He contacted the national associations on the continent in writing and asked them to consider the possibility of founding an umbrella organisation.

When Belgium and France met in the first official international match in Brussels on 1 May 1904, Guérin discussed the subject with his Belgian counterpart Louis Muhlinghaus. It was now definite that the English FA, under its president Lord Kinnaird, would not be participating in the foundation of an international federation. So Guérin took the opportunity and sent out invitations to the founding assembly. The process of organising the international game had begun.

The first FIFA Statutes were laid down and the following points determined: the reciprocal and exclusive recognition of the national associations represented and attending; clubs and players were forbidden to play simultaneously for different national associations; recognition by the other associations of a player's suspension announced by an association; and the playing of matches according to the Laws of the Game of the Football Association Ltd.

Each national association had to pay an annual fee of FF50. Already then there were thoughts of staging an international competition and Article 9 stipulated that FIFA alone was entitled to take over the organisation of such an event. It was decided that these regulations would only come into force as of 1 September 1904. Moreover, the first Statutes of FIFA were only of a provisional nature, in order to simplify the acceptance of additional members. On the day of foundation, the Deutscher Fussball-Bund (German FA) sent a telegram confirming that it would adhere to these Statutes in principle.

Friday, July 1, 2011

History of Pci

A team of Intel engineers (composed primarily of ADL engineers) defined the architecture and developed a proof of concept chipset and platform (Saturn) partnering with teams in the company's desktop PC systems and core logic product organizations. The original PCI architecture team included, among others, Dave Carson, Norm Rasmussen, Brad Hosler, Ed Solari, Bruce Young, Gary Solomon, Ali Oztaskin, Tom Sakoda, Rich Haslam, Jeff Rabe, and Steve Fischer.

PCI (Peripheral Component Interconnect) was immediately put to use in servers, replacing MCA and EISA as the server expansion bus of choice. In mainstream PCs, PCI was slower to replace VESA Local Bus (VLB), and did not gain significant market penetration until late 1994 in second-generation Pentium PCs. By 1996 VLB was all but extinct, and manufacturers had adopted PCI even for 486 computers.[3] EISA continued to be used alongside PCI through 2000. Apple Computer adopted PCI for professional Power Macintosh computers (replacing NuBus) in mid-1995, and the consumer Performa product line (replacing LC PDS) in mid-1996.

Later revisions of PCI added new features and performance improvements, including a 66 MHz 3.3 V standard and 133 MHz PCI-X, and the adaptation of PCI signaling to other form factors. Both PCI-X 1.0b and PCI-X 2.0 are backward compatible with some PCI standards.

The PCI-SIG introduced the serial PCI Express in 2004. At the same time they renamed PCI as Conventional PCI. Since then, motherboard manufacturers have included progressively fewer Conventional PCI slots in favor of the new standard.

PCI (Peripheral Component Interconnect) was immediately put to use in servers, replacing MCA and EISA as the server expansion bus of choice. In mainstream PCs, PCI was slower to replace VESA Local Bus (VLB), and did not gain significant market penetration until late 1994 in second-generation Pentium PCs. By 1996 VLB was all but extinct, and manufacturers had adopted PCI even for 486 computers.[3] EISA continued to be used alongside PCI through 2000. Apple Computer adopted PCI for professional Power Macintosh computers (replacing NuBus) in mid-1995, and the consumer Performa product line (replacing LC PDS) in mid-1996.